Karin Schimke, journalist and poet, talks to Naomi Meyer about her translation of some remarkable love letters.

Karin, you’ve just completed a project in which most Afrikaans and many other bookish people would be interested. What have you been busy with?

In June this year I was asked by Fourie Botha from Umuzi whether I’d be interested in translating, from Afrikaans into English, the letters that Ingrid Jonker wrote to André Brink during their love affair which lasted for two years from 1963 to 1965.

It was an enormous and complex project. There are more than 200 extant billet-doux. Leon de Kock translated André’s letters. It felt right that the translation was done by two people, not only as a practical solution – since there were so many letters – but because it helps to capture two very distinct voices. Leon is an academic, the way that André was. Ingrid wasn’t, and neither am I.

Is it true that André Brink initiated the process? And did he keep all his own love letters to Ingrid Jonker?

Yes, the fact that both sets of letters – almost complete except for a few items here and there – existed together, is really quite remarkable. It’s because of André’s own thoroughness, which, I have come to understand from his widow, was a lifelong habit.

André’s original letters do exist, but they were torn to shreds after Ingrid died. These pieces exist and and form part of Gerrit Komrij's Ingrid Jonker collection in Portugal.

However, there were copies of all André’s letters – because he wrote on carbon paper – and it was these copies, together with Ingrid’s original letters, that he kept in his study in a large brown envelope for fifty years.

Why André wrote on carbon paper, one can only guess at. Thoroughness? Self-consciousness? A desire to read back what he had written to her? Ambition, perhaps? But they also discussed their work with each other and perhaps he wanted to keep a record of his ideas.

What does translating mean to you?

Translation is an imperfect art. If perfection is the aim, you have failed before you have begun. But even if you accept that you are working towards an imperfect goal, you still struggle along the way – when you feel you have to forego shades of meaning, or innuendo or (especially) subtle jokes that are best understood by a mother-tongue speaker.

There are two things that were important to me: I wanted the English text to read as smoothly as possible, but without making Ingrid sound as though she had written in English. I wanted to retain some of the texture of Afrikaans.

How I tried to overcome turning her voice into an English South African one was to steer as close to the source text as possible.

What made it easier was that Ingrid spoke plainly. There was nothing pretentious about her writing, nothing artificial. She was one of those people who “speaks on the page”. Her voice, her moods and her excitement all revealed themselves in simple ways. There was no artifice.

You translated the love letters of arguably the most well-known Afrikaans Romeo and Juliet of the Afrikaans literary world. Did you ever think about this while translating Ingrid's letters?

Oh, I thought about it all the time!

Because of the time constraints on the project we had no time to read the full manuscript before starting the work. The longer I translated, the less sense I had of what was going to happen next and each day’s work was like watching a new petal unfold on a closed bud. It was – and I apologise for the cliché – gripping. When I closed my computer at night, I would wonder what happens next and I’d approach my computer with a sense of anticipation every morning. No, it was not drone work. It held me entirely. It wasn’t mere engagement with words.

Do you, in hindsight, feel that you got to know the person/people who wrote the letters?

There are two parts to this answer.

Because, as I mentioned before, I could not read the entire manuscript before starting, I read André’s letters only here and there to cross-reference or to gain some context where they appeared to have a direct impact on what Ingrid was writing. So only one side of the story was unfolding before me daily.

In that story I felt as though the whole of Ingrid Jonker was being revealed to me. I had a strong sense of her daily preoccupations, her passions, aspects of her personality and themes in her life.

For instance, Ingrid wrote in a fairly haphazard way, changing tack mid-paragraph, inserting brackets which contain what appear to be entirely unrelated stories to the one she was busy with, returning to comment on things she had said earlier, in the middle of some other bit of gossip or news.

I came to see that this fitted a pattern within her life. She was – and this is what André so admired about her – unfettered and unconventional, in quite the most natural way. She was also moody. This is something one knows from other sources, but it is clear in the letters that she is highly emotional. So what is revealed in this correspondence confirms much of what one has gleaned over the years about the person behind the poems.

However, it was only once I read the entire text, front to back, that I felt more of Ingrid became exposed to me. Her letters are of course not simply one-sided ruminations. They’re not diary entries. They are in reaction to – in a dance with – another person. How what André does and thinks and writes affects her, made a fuller and more lustrous picture of her emerge.

I found, for instance, that I saw in her a stoicism I had failed to see when I had only read her letters.

Of course it would be arrogant to say “I know her”, “I know what made her tick”. Every human being remains their own ultimate mystery – to themselves and to others.

She still scratches at me. I wish I could interview her.

Authors are sometimes told not to take a review too seriously, because the opinion is on the text and not on the writer as a human being. Did you feel that you could separate Ingrid Jonker from her love letters?

Ingrid’s poetry was deeply and unashamedly personal. She didn’t, like André, try to grapple great ideas into long novels. Her work feels grounded and embodied. There is a presence and immediacy in both her poetry and her letters and they seem, to me at least, inseparably, undividedly hers.

And yet how she arrives at things, at images and metaphors, remains mysterious and enticing.

When John Kannemeyer wrote about her in Geskiedenis van die Afrikaanse Literatuur he was very dismissive of her poetry and I felt, when I recently reread it, that it did, somehow, also dismiss the person. It is clear to me from the letters that being dismissed, sidelined and even reviled was part of Ingrid’s experience of the world. She was not a conformist. I think she had no idea how to be. And being non-conformist is difficult even under the easiest circumstances – and her circumstances were never anything but difficult.

Who was Ingrid Jonker?

She was, first and foremost, a struggling single mother working in soul-destroying jobs.

There is much to read about Ingrid – her politics, her poetry, her clashes with her father, her relationships and friendships. But the single most draining and wearying fact of her life – that every day was a physical, spiritual and financial struggle – has been mostly overlooked or underestimated.

And yet it goes to the heart of what it is like to be a woman in a world in which men are easily able to pursue and nourish their talents, while women have a great number of little hurdles and expectations to negotiate and hoops to jump through. Sometimes, if they are lucky, they can break off little in-between moments to practise their art. Ingrid wrote her poems on the bus and dreamt of having a study like André did.

She wants to be a good mother and she wants to be a good writer. But, in fact, she is a whirling dervish, rushing to work, rushing to fetch her daughter, struggling to pay the rent. And so utterly alone in the world, in spite of a large and mostly warm group of friends. Her daily struggles – like all single mothers’ – are mostly invisible to the outside world and are hers alone. I think they were too hard, too many and too insurmountable. She had talent and success, and she committed suicide, so we remember her with great empathy and sadness, but I couldn’t help thinking about how many Ingrids there are around us every day and we don’t notice them. We don’t know that they, like Ingrid, have great dreams, have unexplored talents or just a desire to live a life of dignity without the constant merciless struggle against tiredness and poverty and the crampedness of life that seems to have no obvious prospects.

I think Ingrid was that person. But she was also cheerful, sharp, witty, warm, as well as unconventional and unpredictable. It feels to me as though André saw only these things in her, not the whole person – not the ungovernable struggle of daily life. His little cheques here and there helped to some degree, but they didn’t take account of the relentlessness of a single mother’s daily slog.

How did you translate her letters - and did you translate her poems as well?

I translated her letters in as straightforward a way as possible. Sometimes things were difficult to understand because of her haphazard and flighty style, and I tried as far as possible not to interpret, but simply to reflect. I did not translate her poems. The editorial team took a decision to use the Afrikaans Vlam in die sneeu as the source text for the English, but to use Black butterflies (selected poems translated by André Brink and Antjie Krog) as the source text for her poems. This means that sometimes there is a difference between the Afrikaans poems, which are often in their earliest versions, in Vlam in die sneeu, and those that appear in the English text.

Did you use any other books/texts as resources or aids for your translations?

Apart from my dictionaries, the books beside my computer were Petrovna Metelerkamp’s Ingrid Jonker – A Poet’s Life, André’s memoir A fork in the road, and Louise Viljoen’s Ingrid Jonker.

Did André Brink and Ingrid Jonker write to each other solely in Afrikaans?

Yes. They always wrote in Afrikaans, but the letters are peppered with other languages. Ingrid enjoyed Walt Whitman and quoted him – and other American poets – often. Both read prodigiously in Dutch.

André also quoted texts from other languages. At one point, when things are stiff (but always polite and loving) between them in the letters, following a falling-out, Ingrid reminds André in a rather curt way that she doesn’t read French.

I read two feelings into this, both of them quite well tucked beneath the surface of her letters: a sense of inferiority about the lacunas in her education – of which there were a great many, and especially in relation to André’s, which was incredibly rich and privileged – and an irritation with his assumptions that everyone was as educated as he.

Trying to decide what to translate and what not to translate caused the translation and editorial team quite a number of headaches. Both the Afrikaans and the English texts are meant for a general readership and a decision was taken early on not to burden readers with explanatory annotations and footnotes. Also, Leon and I could not translate every non-Afrikaans quote, passage or poem into English. And, of course, Ingrid and André wrote fast and passionately and often quoted things from memory, so there are inaccuracies in quotes too. It was quite a task and it really came together because of really dedicated teamwork between the translators and editors.

How long did their relationship last?

How long did their relationship last?

The relationship lasted two years and it was on-again, off-again, as was her relationship with Jack Cope.

My strong sense was that she would have liked things to be different. She wanted stability and clarity. I don’t think she would necessarily have been able to provide it for a partner in return – that she was fiery and flighty and “difficult” seems evident in so much of what remains about her – but I think it was her greatest need: to have someone she could reliably lean into and on; some solid ground beneath her feet.

Much of the arc (and many of the details of their relationship) is available to the reader of Flame in the snow, but much of it is enticingly missing. They spent a few “stolen times” together for weekends, or days, away and – disastrously – overseas in Paris and Barcelona – and during those times they do not correspond so we are not privy to what “went down” – and a lot went down! The allusions to them in the letters that follow those times are tantalising.

There are also phone calls and tapes that they made for each other. So some of the detail is lost. And yet these “holes” do not jeopardise the text as a whole.

Do you think that both writers loved their own words and ideas – and that a real flesh-and-blood human could perhaps only be a disappointment?

Oh yes! Please allow the amateur psychologist in me to answer this. There is so much projection going on between them – but especially from André towards Ingrid – that this correspondence also reads like an abject lesson in how blind we are when we’re in love.

Ingrid very clearly embodies a potent desire in André to break free from a staid, bourgeois existence, and he says as much, often, but obviously without any insight that he is indulging in fantasy.

André, on the other hand, makes what I think are sincere promises to Ingrid – in complete denial of the blatant impossibility of their situation – and while Ingrid takes a while to trust him, she, too, throws herself wholeheartedly into something which, on even the most superficial inspection, shows itself to be a mere chimera.

Just how “mad” their connection is manifests in the shared fantasy of creating a child – a “moesiekind” – together.

They have imbued each other and each other’s words with the magical properties each most needs. That their love affair was one of those grand life set-ups for a hard lesson learned is completely invisible to them.

They were young. We’ve all made these monstrous mistakes of projection and denial. They don’t always turn out quite as badly as Ingrid and André’s story, though.

I think this is partly why this is such a gripping book: we recognise ourselves in their story. Our silly, cheesy, hopeful, ambitious selves. Our best selves. Our most vulnerable and naive selves.

Translation is in the news – I’m thinking of the Open Stellenbosch debate, for example. Can translation help to open up the worlds of other people?

Where else could it begin? At being human of course, but how do we access one another’s humanity when we have a single, flawed, common language to do it in? We need multiple flawed common languages – and still our worlds will remain partially shut to one another. It is part of the human condition to be trapped inside language.

Perhaps the simplest place to start is not with translation, but with each person undertaking to learn another language.

Mother-tongue speakers are – for the most part – friendly and welcoming to people who attempt to communicate with them in their language, so why are we so afraid to try? It’s laziness. English wins and the more it wins the more people speak it and the less they speak their own languages or bother with others. If you speak the culturally and economically dominant language, why would you bother yourself with others? It breeds a kind of arrogance, hegemony and laziness. Language imperialism.

So the challenge – for me all social challenges, actually – begin in the tiny universe of the personal. Firstly, if you can translate something you think is worthwhile translating into any language, translate it.

I once wrote an article about the importance of reading to children and a woman wrote me a letter (an old-fashioned one that came in the post!) from the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands and said that it was so full of useful advice that she would like to translate it into Zulu. She did. She wasn’t paid by anyone, but the article was translated and published and presumably someone, somewhere who had been unable to access it before was able to read it in their home language. Translation seems to me an act of love and a high sense of responsibility to the difficult act of learning to be human in spite difference.

Secondly, we could learn another language. Okay, that’s easier said than done, but it’s not impossible. Learn vocabulary, if you can’t start with the task of sentence construction. Learn some greetings and learn to respond when someone says “Uthetha isiXhosa!?” with surprise and delight and you can answer them, brokenly, “Ewe, ndiyay’ qondi kancini” – “I understand a little.”

It’s hard, but God, most of the time we all feel so helpless and clueless about how to reach across the various abysses that divide us. Here is one that is breachable with just the tiniest bit of effort.

I was fascinated, during the translation of the Brink-Jonker correspondence, by how actively and easily writers then engaged with other languages. And because of many of the Sestigers’ natural curiosity about other languages, great works of world literature are available in Afrikaans.

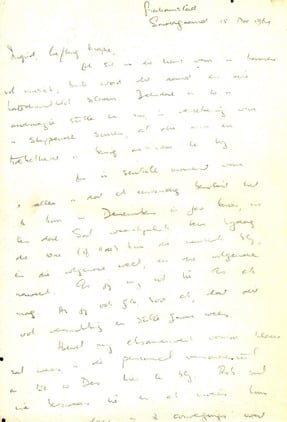

This is a photo of a lock of Ingrid Jonker's hair, which she cut off in André Brink’s presence. There is reference to this in their correspondence. Karina Szczurek, André's wife, recently discovered the lock in one of his copies of Ingrid's collection of poetry, Smoke and Ochre (Rook en Oker).

Photo by Karin Schimke.

What was the most interesting aspect of this project?

So many things. I was fascinated by just how unusual Ingrid Jonker was and how lonely it must have been. She would have been considered a little eccentric now, but back then she must have had to fight back a deluge of disapproval about her way of life daily. She was so independent, so outspoken and constitutionally unable to conform that I think life must have been pretty hard for her.

I was fascinated by the Cape Town that emerged from the letters and it led me on a mad hunt for old photographs and details. I wrote a feature-length article about Ingrid’s Cape Town for High Life magazine as a result of that fascination.

I was interested in the dynamics of the mother-daughter relationship. Ingrid tried so hard to be a good mother, but although she was loving and always tried to do the right thing she was also erratic and unreliable. I think an erratic parent is one of the hardest things to negotiate as a small child and I really felt for little Simone. It must have been bewildering for her.

I was interested in comparing how much women have been liberated from the kinds of bonds Ingrid was constrained by. Sadly, not very much, by my calculations.

As for the act of translation, the usual sorts of questions arise: To be literal or interpretive? To remain as close as possible to the original, or to feel the freedom to create newly?

Always these questions were answered by the text itself: I wanted merely to act as interpreter. I wanted to tell English readers what Ingrid had said in Afrikaans. I wanted them to come to the text with the benefit of their own curiosity.

Ingrid’s voice is vivid and that was all I wished to convey. No analysis. No interpretation. Just the voice of Ingrid.

Did you – an acclaimed poet yourself – ever want to change Ingrid Jonker's words while you were translating?

Actually, the instinct I had to repress most was the journalistic one. “Jislaaik, Ingrid, this is a knotty mess, let me straighten out this paragraph for you. Let me correct your spelling and fix your punctuation, which really, really sucks at times!” But I mostly didn’t. I simply read and read and reread every confusing piece until it made sense and then I translated it. Ingrid’s sense is there and once you “hear” her voice, you hear her sense. It’s scatty and kooky and wild and at times infuriating, but she cannot be accused of not making sense, even if it isn’t sense in the way a journalist likes it: neatly packaged and perfectly punctuated little paragraphs that flow from one to the other.

Who was the man to whom Ingrid Jonker wrote her letters?

He comes across as warm, loving, generous and kind. He had an astonishing work rate and an insatiable appetite for everything – books, music, knowledge, food, sex. In fact, he seems driven by these appetites. They are appropriate appetites in people under twenty, in any age, really, but I think sometimes they rule us destructively and things get broken.

You cannot hold someone’s youth against them. He was dithering and confused and sometimes stubbornly myopic and lacking in self-insight. But he was young and had been afflicted by the hopeless madness of love. It happens.

Who worked with you on this project?

This project’s lynchpin was Francis Galloway, the Afrikaans editor, who made herself available for queries from the translation team. I cannot imagine who else might have been able to handle her job with the same grace and humour and a bottomless, mind-boggling knowledge on the subject of the Sestigers. She is like a walking encyclopaedia and full of fascinating anecdotes and tidbits. And super-quick about answering e-mails.

Lynda Gilfillan was the English editor. She had to plait together what was, in essence, three texts into one aesthetic whole: the Afrikaans, the André part and Ingrid part. She had to ensure fluency, consistency and flow. I think she did a magnificent job of creating a wholly independent and readable English text. I thoroughly enjoyed reading the end product.

Could André Brink and Ingrid Jonker have grown old together if she had not committed suicide?

No.

- Letters and photos made available by the publisher.

- The special edition of Flame in the Snow is now available.

The post Flame in the Snow – the love letters of André Brink and Ingrid Jonker appeared first on LitNet.